-->

NJ Bridgewater

-->

Mesopotamia – The

Birthplace of Civilization

Mesopotamia is widely

regarded as the birthplace of civilization. As Marc Van De Mieroop remarks in The

Ancient Mesopotamian City, it took a long time before the first ‘cities’,

as we now understand the term, emerged, with the first settlements in southern

Mesopotamia emerging around 5500 BC and the first cities appearing around 3500

BC as the culmination of a long process of development.[1]

The earliest cities, according to Mieroop, contained ceremonial centres, or

temples. He disputes the conclusion that religion was central to the formation

of cities, which was argued by Paul Wheatley.[2]

Rather, he argues, these temples provided a managerial role in the local economy,

with religion providing the authority to extract agricultural resources from

the surrounding countryside.[3]

He also discusses the possibility that long-distance trade led to the emergence

of cities, as proposed by Jane Jacobs (1969).[4]

Mieroop’s own conclusion is that agriculture led to social stratification, with

social classes replacing kin groups, and with upper classes taking hold of the

social hierarchy and administration, leading to the creation of the priesthood

which dominated the cities.[5]

The priesthood was buttressed and supported by the development of writing and

bookkeeping, which allowed the temples to serve as centres for economic

redistribution.[6]

Gods and religious cults, in Mieroop’s view, merely serve as the justification

and backdrop for this largely economic structure.[7]

This view is flawed, however, by discounting the real nature of religion and

its unifying role in the formation and maintenance of society and social bonds.

He fails to consider that religion, economics and culture are intimately bound

together and cannot be separated. Rather than being a separate aspect of life,

religion is, in essence, the glue that holds all aspects of society together,

and the core of its values and norms. The cities of Mesopotamia emerged for

economic and social reasons, but with religion, which was at the heart of

hunter-gatherer life, as a central factor. Just as ancient hunter-gatherer

bands gathered together to trade and, mostly likely, engage in spiritual and

religious practices, the development of an organized priesthood and temples

gave the impetus for the development of the core of the first cities, around

which large collections of neighbourhoods and other institutions emerged.

_(14767240352).jpg) |

| Ancient Sumerians going to war[8] |

These ancient Sumerian

cities are the models for and antecedents of the modern cities we live and work

in today (or don’t, if we live in the countryside). The word civilization

ultimately derives from the Latin word civitas, which means ‘city’. The

term, with the meaning of ‘the state of being civilized and free from the

condition of barbarity’, was first recorded in 1772.[9]

The equivalent term to civitas in Ancient Greek was polis (pl. poleis),

which can also mean the body of citizens. For the Greeks, a city was not merely

a collection of buildings, which they called asty. Rather, a polis

included a number of characteristics, including self-governance and autonomy

(characteristic of city-states), an agora (the central social hub and financial

marketplaces), an acropolis (a citadel housing a temple), coinage, and other

elements.[10]

The Sumerian city was ruled by a priest-king or governor called an Ensi,

which was largely synonymous with the term lugal ‘king’ during the Early

Dynastic Period (c. 2800 – 2350 BCE). As with the Greek city, a temple or

sacred area was at the heart of the city. Sumerians built great ziggurats in

the form of terraced compounds of successively receding levels.[11]

While the concept of sacred

kingship might contrast sharply with the later Greek concept of democracy, more

ancient Hellenic peoples, such as the Mycenaeans, conformed to the Sumerian

model of sacred kingship, as did the Egyptians, who also began to build cities

and temples in the ancient Fertile Crescent. This is evidenced by the elaborate

burial chambers used in Mycenaean cities and in Ancient Egypt, as well as the luxurious

items buried with kings and nobles. The Death Mask of Agamemnon (c. 1550 – 1500

BC) is a prominent example, as are the pyramids of the Egyptian Pharaohs (c. 2589

– 2504 BC) and their burial chambers in the Valley of the Kings. Several main

elements of the ancient or original pattern of cities may thus be surmised: an

organized religion and temple structure, public spaces, kingship or

priest-kings who represent the deity, rule of law, trade and barter, a unified

culture, writing and scribes, agriculture and social stratification. Writing,

indeed, was characteristic of all the great Old World civilizations, including

the Chinese (who used the so-called ‘Oracle Bones’), the Egyptians, who used

hieroglyphs, and the Myceneans, who used a syllabic script called Linear B. The

Sumerians, who invented cuneiform, set the pattern for the scribal system,

which greatly facilitated record-keeping, administration and trade. Writing

also allowed for the formalization of contracts, title deeds and property

rights. It could also be used to record rituals, myths, legends and sacred

texts, as well as codes of law. The rule of law, which is essential for

wealth-building and capital accumulation, indeed, was integral to civilization.

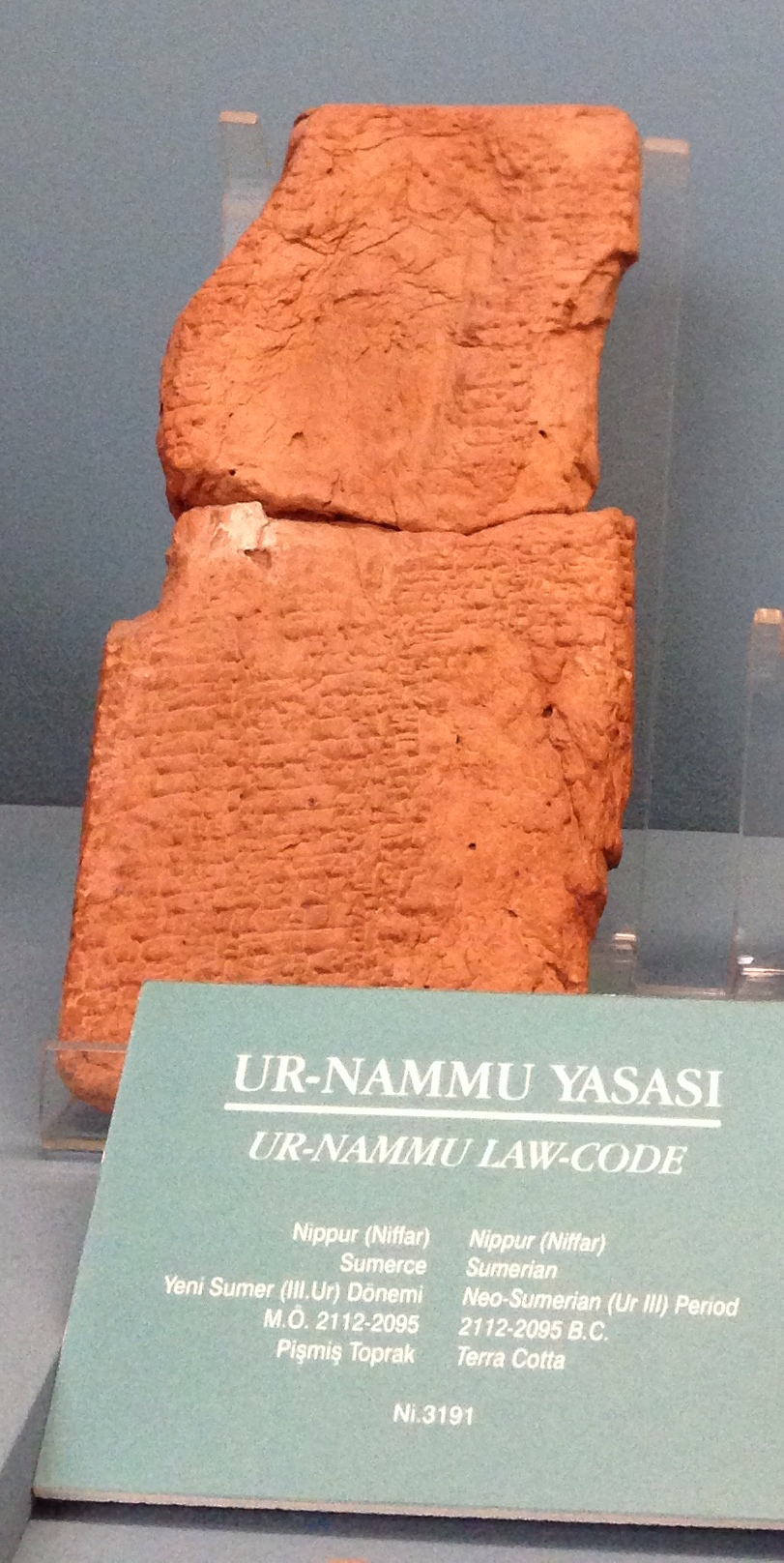

|

| The Code of Ur-Nammu[12] |

The earliest recorded code of law, which survives to this day, was the Code of Ur-Nammu, which dates back to circa 2100 – 2050 BC. Initially discovered and translated in 1952, the text records the laws of King Ur-Nammu of Ur, who reigned circa 2112 – 2095 BC.[13] While earlier law codes existed, e.g. the Code of Urukagina, Ur-Nammu’s code is the earliest of which the text has survived, preceding the much-more-famous Code of Hammurabi (c. 1754 BC) by three centuries.[14] Interesting features of the code include the if-then structure, fines of monetary compensation for bodily damage rather than the lex talionis (‘eye for an eye’), and the death penalty for murder, robbery, adultery and rape. All of these elements would sit comfortably within a modern code of law. The social structure revealed by the text, however, is somewhat different from today, with the lugal ‘king’ at the head of society, followed by the lu ‘freeman’ and the arad / geme (male/female slave).[15] Slavery was a common ancient institution, which seems to have its origins in the roots of civilization and may be a result of early social stratification and warfare. There are several forms of slavery, including chattel slavery (in which people are treated as possessions), bonded slavery (where people serve as slaves until a debt is paid off) and forced labour (often resulting from imprisonment). Slavery is rare among hunter-gatherers because it depends on the existence of economic surpluses, which resulted from the Agricultural Revolution.[16] While the origins of slavery are unknown, chattel slavery may have originated as a result of military defeat, with captured peoples of different tribes or cities being turned into slaves, and bonded slavery probably emerged with early trade and commerce, where debts or other liabilities could lead to bondage in payment for money/services owed. In any case, slavery was a universal institution, practiced by all cultures and civilizations, and people of all races and backgrounds have been subjected to its vicissitudes at one time or another. We can only be grateful for the fact that the British Empire, which had done so much to spread the rule of law, trade, technology and the fruits of civilization worldwide, abolished the slave trade across its vast empire with the Slave Trade Act 1807, as well as the Slavery Abolition Act 1833, which did so much to remove this baneful (and baleful) institution from mankind. While slavery has continued, in one form or another, to this day, it was the British Empire which made the slave trade and slavery illegal, and which removed it as an institution within almost all nations. This is due, in no small part, to English and British values. As John Locke wrote, as far back as the 17th century:

“Slavery is so vile and miserable an estate of man, and so directly opposite to the generous temper and courage of our nation; that it is hardly to be conceived, that an Englishman, much less a gentleman, should plead for it.”[17]

Coinage and Kings

One of the greatest

innovations by early cities and states was the creation of coinage and money as

we recognize it today. The earliest coins can be traced to King Alyattes of

Lydia (c. 600 BC). Lydia, located in Anatolia (modern-day Turkey), was an

ancient kingdom which existed from 1200 BC to 546 BC, covering, at its greatest

extent, the whole of western Anatolia.[18]

According to Paul Einzig, it was Herodotus who identified Lydia as the origin

of coinage. This was preceded, however, by a number of other methods of

maintaining and exchanging value, including the creation of rudimentary ingots

or dumps of precious metal, which were used in Knossos on Crete during the

second millennium BC.[19]

I have addressed the topic of the origin of coinage several times before,

including in Gold: 10 Ways to Make Money Using Gold, which is available

in PDF format. In this work, I noted that gold coinage was often associated

with King Croesus of Lydia, (595 – c. 546 BCE), who reigned for 14 years.[20]

Renowned for his great wealth and splendour, the phrase ‘rich as Croesus’ or

‘richer than Croesus’ later arose, indicating that someone is incredibly wealthy.[21]

In this short book, I also noted the possibility that Pheidon II (d. aft. 650

BC), King of Argos, was the first to coin silver money—Lydia’s coinage was made

from electrum (an alloy of gold and silver)—while China began to mint Ying yuan

gold coins around the 5th or 6th centuries BC.[22]

Both gold and silver continued to be used for coinage for centuries. These two

metals had a number of advantages, and I go into the advantages of gold in more

detail in Gold: 10 Ways to Make Money Using Gold. In the same work, I

also mention several later developments, including the Florentine florin, which

was a standard gold coin used across Europe during the Middle Ages, the English

‘crown of the double rose’ (valued at 5 shillings), and the 22-karat ‘crown

gold’ which was continually produced until 1662 AD. These were replaced by the

guinea, worth approximately one quarter ounce of gold (about £246 in modern

currency).[23]

The name ‘guinea’ comes from the Guinea region of West Africa, where much of

the gold for the coins originated.[24]

|

| Electrum coins from Lydia (6th century BC)[25] |

The creation of money, as we

know it, was a significant step—both in the development of civilization, and in

the growth of wealth worldwide. Despite arguments to the contrary, the

development of civilization brought greater wealth and prosperity to mankind as

a whole. While greater equality and equity existed during the time of

hunter-gathering, in the Palaeolithic and Neolithic eras, equality is not

always the ideal. We can make everyone on Earth equal by reducing them to utter

poverty and destitution. That is, after all, the effect of communism which,

whenever and wherever it is put into practice, tends to make the majority of

the population equally poor, while a small, party elite reigns supreme.

Capitalism, wherever practised, leads to the opposite result. While there are

still a minority of rich people who hold most of the power and are extremely

wealthy, the vast majority of people also have a higher standard of living and

more opportunities to better their condition and grow wealthy themselves. This

uneven distribution of wealth under capitalism, we may note is due to the Pareto

principle, in which 80% of the land/wealth tends to be controlled by 20% of the

people,[26]

seems to be a result of human nature itself, rather than any deliberate

manipulation or exploitation. People are, ultimately, naturally different, and

differences in individual abilities, skills and choices result in different

outcomes. “The laws of the distribution of wealth,” the economist Vilfredo

Pareto (1848 – 1923) writes, “evidently depend on the nature of man and on the

economic organization of society.”[27]

Nor should we imagine the various income brackets as being static and

immovable. As Thomas Sowell explains, “studies that follow actual

flesh-and-blood individiuals over time” find that “most working Americans who

were initially in the bottom 20 percent of income-earners, rise out of that

bottom 20 percent” and “more of them end up in the top 20 percent than remain

in the bottom 20 percent.”[28]

The development of ancient cities

meant that greater numbers of people could congregate in one area, which became

a hub for trade, artistry, and craftsmanship, as well as the exchange of ideas,

culture, technology and information. As cities became linked by the first early

empires and kingdoms, trade networks could be expanded, allowing for even

greater opportunities for free movement, trade and the exchange of wealth and

knowledge. While ancient peoples often did suffer from poverty and deprivation,

and farmers were often subject to the rigours of environmental disasters (e.g.

floods, droughts, etc.) and war, the opportunities for trade and development

were great. And the greater the empire, the greater the opportunities. When the

Romans invaded Great Britain, starting in 43 BC, and eventually incorporated it

into their burgeoning empire, the British Isles were opened to a new vista of

culture, technology, trade and civilization. Many benefits followed, including

the development of new towns, the construction or roads and other

infrastructure, the introduction of the more efficient Roman plough, imported

pottery and metalwork, new building methods, window panes, latrines, real

architecture, sculpture and representational art, as well as Roman capital,

which helped to develop the British economy.[29]

During the Pax Romana, the great golden age of Roman civilization,

Britain enjoyed the benefits of peace and prosperity and, furthermore, the

Romans built a major port on the Thames, which came to be known as Londinium

(i.e. London).[30]

A similar unifying and economically-beneficial effect occurred with the spread

of the expansion of British trade, culture and the rule of law during the 18th

and 19th centuries. Indeed, as Niall Ferguson argues, the “combination

of free trade, mass migration, and unprecedented overseas investment propelled

large parts of the British Empire to the forefront of world economic

development”, while also building infrastructure, the rule of law and numerous

economic investments and improvements in places as far flung as East Africa and

India.[31]

|

| The British Empire (1910)[32] |

Colonization (and colonialism) have brought tremendous benefits to mankind. As Greeks and Phoenicians settled new cities across the Mediterranean, for example, and colonised remote islands, vast maritime trade networks were formed, allowing for the trading of goods, resources and knowledge across a vast area. The Persian Empire opened up even greater vistas for trade and commerce, as did the later Macedonian, Roman and Byzantine Empires, as well as the Islamic Caliphates (e.g. the Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphates) and the Mongolian Empire. Vast areas of the world were joined and fused together into one great free trade zone where people could move unencumbered across vast swathes of the world. As Peter Frankopan writes in The Silk Roads: A New History of the World, the Persian Empire developed “a road network that linked the coast of Asia Minor with Babylon, Susa and Persepolis”, which “enabled a distance of more than 1,600 miles to be covered in the course of a week”, resulting in the creation of “a land of plenty that connected the Mediterranean with the heart of Asia.”[33] The Persian Empire was, furthermore, “a beacon of stability and fairness” characterized by tolerance of minorities and justice.[34] Imperialism, when viewed through the purely ideological and Marxian scope of power dynamics, may seem negative and injurious, as it involves one group, family, individual, tribe or nation taking over and controlling other tribes, nations, etc. Seen purely through this skewed and ideological lens of power and subjugation, ruler and ruled—it seems to be negative. The reality, however, is far from the case. Empires allow for the spread of the rule of law, culture, technology, knowledge, commerce and industry on a vast scale. The larger the empire—the larger the civilization—the more benefits it bestows on its inhabitants. This is dependent on a number of factors, of course, including the building blocks of civilization and capitalism which we have already mentioned. When these are ignored or fall to ruin, the empire and its civilization likewise fall to ruin. This is the example of history.

[1] Marc Van De Mieroop (1999) The Ancient

Mesopotamian City (Oxford: Oxford University Press), p. 23.

[2] See:

Mieroop (1999), p. 24.

[3] See:

Mieroop (1999), p. 24.

[4] See:

Mieroop (1999), p. 25.

[5] See:

Mieroop (1999), p. 27.

[6] See:

Mieroop (1999), p. 27.

[7] See:

Mieroop (1999), p. 27.

[8] Image

source: Ur excavations, 1900 (public domain). URL: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/8/8e/Ur_excavations_%281900%29_%2814767240352%29.jpg

(accessed 04/07/2018).

[9] See:

Douglas Harper (2001-2018) civilization (n.), Online Etymological Dictionary.

URL: https://www.etymonline.com/word/civilization (accessed 03/07/2018).

[10] See:

Polis (Wikipedia article). URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polis

(accessed 03/07/2018 11:56 AST).

[11] See:

ziggurat (Wikipedia article). URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ziggurat

(accessed 03/07/2018 12:11 AST).

[12] Image

source: Ur-Nammu Code, Istanbul, uploaded 1 August 2014 by oncenawhile (Creative

Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication). URL: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/71/Ur_Nammu_code_Istanbul.jpg

(accessed 04/07/2018). For more information on the license, see: https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/deed.en

(accessed 04/07/2018).

[13] See:

Code of Ur-Nammu (Wikipedia article). URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Code_of_Ur-Nammu

(accessed 03/07/2018 12:37 PM AST),

[14] See: Code

of Ur-Nammu (Wikipedia article).

[15] See:

Code of Ur-Nammu (Wikipedia article).

[16] See:

Slavery (Wikipedia article). URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Slavery

(accessed 03/07/2018 12:46 PM AST).

[17] See:

John Locke, Two Treatises of Government, Book I, Chap I. §. 1. URL: http://www.johnlocke.net/two-treatises-of-government-book-i/

(accessed 03/07/2018).

[18] See:

Lydia (Wikipedia article). URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lydia

(accessed 03/07/2018 13:01 AST).

[19] See:

Paul Einzig (2014) Primitive Money: in its Ethnological, Historical and

Economic Aspects (Amsterdam: Pergamon), p. 217.

[20] NJ

Bridgewater (2017b) Gold: 10 Ways to Make Money Using Gold (Published

online: Jaha Publishing), p. 15. Available for purchase at: https://gumroad.com/l/eYACw

(accessed 03/07/2018).

[21] Croesus (Wikipedia

article). URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Croesus (accessed 15/10/2017 1:42

PM AST).

[22] See:

Bridgewater (2017b).

[23] See:

Bridgewater (2017b).

[24] See:

Guinea (coin) (Wikipedia article). URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guinea_(coin)

(accessed 05/07/2018 16:10 AST).

[25] Image

source: Kings of Lydia. Time of Kroisos. Circa 561-546 BC. From the Ronald

Cohen Collection. Ex Tkalec (18 February 2002), lot 81. (GNU Free Documentation

License, Version 1.2). URL: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/5/5c/Kroisos_BMC_31.jpg

(accessed 04/07/2018). For more information on the license, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/GNU_Free_Documentation_License

(accessed 04/07/2018).

[26] See:

Pareto principle (Wikipedia article). URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pareto_principle

(accessed 05/07/2018 16:18 AST).

[27] See:

Vilfredo Pareto (1897) The New Theories of Economics, Journal of Political

Economy, Vol. 5, No. 4 (Sep., 1897), pp. 485-502. URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1821012 (accessed

04/07/2018).

[28] See:

Thomas Sowell (2013) Economic Mobility, Townhall.com, Mar 06, 2013 12:01

AM. URL: https://townhall.com/columnists/thomassowell/2013/03/06/economic-mobility-n1525556

(accessed 05/07/2018).

[29] See:

Thomas Sowell (2008) Conquests and Cultures: An International History

(New York, NY: Basic Books), p. 25.

[30] See:

Sowell (2008), p. 25.

[31] See:

Niall Ferguson (2003) British Imperialism Revisited: The Costs and Benefits of

“Anglobalization”, Historically Speaking: The Bulletin of the Historical

Society, April 2003, Volume IV, Number 4. URL: https://www.bu.edu/historic/hs/april03.html

(accessed 05/07/2018).

[32] Image

source: An elaborate map of the British Empire in 1910, marked in the

traditional colour for imperial British dominions on maps, by Arthur Mee, The

Childrens' Encyclopaedia. Vol. 2. (public domain). URL: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/3/32/Arthur_Mees_Flags_of_A_Free_Empire_1910_Cornell_CUL_PJM_1167_01.jpg

(accessed 05/07/2018).

[33] See:

Peter Frankopan (2016) The Silk Roads: A New

History of the World (New York, NY:

Vintage Books), p. 4.

[34] See:

Frankopan (2016), p. 4.

No comments:

Post a Comment