NJ Bridgewater

25 November 2018

The Golden Age of Sound

Money:

European Exploration, the

Victorian Era and the Gilded Age

Whenever sound money is

widely used, prosperity and economic growth must exist. This is due to the fact

that sound money allows people to save up capital, which can then be used to

create businesses, facilitate trade, and purchase real-world assets, such as

real-estate. It also constrains governments from over-spending, allowing for

state stability. Furthermore, it discourages frivolous spending, because money

has greater value when kept rather than spent; conversely, fiat currency has

high velocity and is like a hot potato—if you don’t spend it, it loses value. In

such circumstances, great artists, litterateurs, architects and musicians,

therefore, tend to arise, and are patronised by kings, nobles and merchants who

appreciate high art and low-time-preference entertainment. The opposite can be

seen where the currency is debased or inflated, as in the case of the later

Roman Empire, where bread and circuses abounded, as the borders of the empire

collapsed, the economy stagnated, and the people were robbed of their wealth

through requisitions and high taxation.

The term ‘Gilded Age’ was

coined by Mark Twain to refer to the late 19th century (i.e. 1870 –

1900). This was a particular age with particular characteristics, but it formed

part of a much wider time period embracing the Age of Discovery or ‘Age of Exploration’

(1418 – 1779), the Industrial Revolution (1760 – 1840), the Victorian Era (1837

– 1901), the Gilded Age (1870 – 1900), and La Belle Époque (i.e the ‘Beautiful

Era’) (1871 – 1914), ending with the outbreak of World War I and the

establishment of the Federal Reserve System in the United States in 1913 with

the Federal Reserve Act (December 22, 1913). This age could be said to have

begun with the reign of Prince Henry the Navigator (1394 – 1460), the fourth

child of King John I of Portugal. He made a number of important contributions,

including the capture of the Moorish port of Ceuta in northern Morocco, which

had long been a base for Barbary pirates who raided the coast, depopulating

entire villages and selling them in the African slave trade.[1]

This was followed by exploration of the coast of Africa, which was then unknown

to Europeans, aiming to find the source of the West African gold trade and

stopping pirate attacks on the Portuguese coast.[2]

Alternatively, the era could also be said to have begun with the end of the

Spanish Reconquista, which ended with the fall of the Nasrid kingdom of Granada

on January 2, 1492, followed by Columbus’s exploration of the Americas in the

same year.[3]

|

| Silver peso of Philip V |

This era was characterised

not only by a huge expansion in knowledge, economic growth and the building of

new empires, colonies and technologies, but also by an important factor which

ran throughout, ending in 1914, the use of real, sound money. This era

coincided with the usage of the Spanish silver dollar (1598 – 1869), which was

used from the America in the West to China in the East, serving as one of the

first world currencies, ending with the United States Coinage Act of 1857, and

the adoption in Spain of the peseta (equal to 4.5 grams of silver or 0.290322

grams of gold) in 1869.[5]

The introduction of high-silver-content coins in Spain was inspired by the

introduction of the Guldengroschen, originally minted in Tirol, Austria, in

1486, with a level of purity (0.937%) not seen in centuries, followed by the

introduction of the half-guldengroschen, valued at 30 kreutzer (with each

kreutzer being worth about 4.2 Pfennig, i.e pennies, and, from 1559, with 60

kreutzer being worth 1 gulden or guilder).[6]

The word ‘dollar’ comes from the Thaler (with Thal meaning ‘valley’,

equivalent to the English word ‘dale’). The first Thalers were minted by Louis

II of Hungary (1506 – 1526) which was called the Joachimsthaler, weighing one

ounce in weight (27.2g).[7]

This was followed by the imperial Reichsthaler (1566 – 1750), which was defined

as containing 400.99 grains of silver (25.984g), becoming the standard coin of

account for the entire Holy Roman Empire until the middle of the 18th

century. Another currency which spanned this period was the Portuguese real

(plural réis or reais), which was first introduced by Dom

Ferdinand I (1345 – 1383), called “the Handsome”, King of Portugal, being

originally a silver coin valued at 120 dinheiros, 10 soldos, or ½ libra.[8]

One soldo (from the Latin solidus) was equivalent to 12 dinheiros, and

twenty soldos was equal to one libra.[9]

The Portuguese dinheiro

system was based on the only Roman system of the librae, solidi and denarii, reintroduced

to Europe by King Charlemagne in the 9th century AD.[10]

The Portuguese real weighed 3.5g of silver (about $50 USD), being almost the

same weight as the Venetian gold ducat.[11]

The Venetian gold ducat, introduced by the Great Council of Venice in 1284 AD,

contained 3.545 grams of 99.47% fine gold, which was the highest purity of gold

which could be produced at the time, until they were finally discontinued when

Napoleon ended the Venetian Republic in 1797 AD.[12]

In my short information guide, Gold: 10 Ways to Make Money Using Gold, I

give a brief summary of the history of gold coinage, including the Florentine

florin and the English guinea, which were both contemporaneous with the

Venetian gold ducat.[13]

I wrote: “In the Middle Ages, the Florentine florin, struck from 1252 to 1533

with no significant change, was a standard gold coin which was used across

Europe. Composed of 54 grains of ‘fine gold’ (3.5 grams), it was worth

approximately $140 U.S… Henry VIII’s monetary reform of 1526 resulted in the

creation of the crown, originally called ‘the crown of the double rose’, which

was valued at 5 shillings. These were minted of 22-karat ‘crown gold’, and it continued

to be produced until 1662. These were then replaced by the guinea, which was a

coin of approximately one quarter ounce of gold, minted in Great Britain

between 1663 and 1814 CE. The name

‘guinea’ derives from the Guinea region of West Africa, where much of the gold

used to produce the coins was sourced. The first English machine-struck gold

coin, it was originally worth one pound sterling (i.e. 20 shillings); however,

due to a rise in the price of gold relative to silver, it was at times worth 30

shillings. From 1717 to 1816, nevertheless, its value was officially fixed at

21 shillings. Guineas are currently not

recognized as legal tender. However, as they contain 22-karat gold and weigh

8.3g, or a quarter of an ounce of gold, one guinea is equivalent to about £246

GBP (in 2017).”[14]

| Five Guinea coin (1688) |

The era which we are

outlining, in which gold and silver standards prevailed, and in which central

banks did not exist, spans from about 1418 or 1492 until 1914, when World War

One ended and the era of fiat currency, hyperinflation, Keynesian economics and

boom and bust began. We might well describe this whole period of time as one

Grand Gilded Age, or perhaps the Golden Age of Sound Money, during which the

birth of a new world—a new technological and advanced modern era took shape and

formed. It was characterised, moreover, by the birth and expansion of the

British Empire, which, by 1913, held sway over some 412 million people, which

was 23% of the world’s population and, at 13.7 million square miles (35.5

million square kilometres), covered about 24% of the Earth’s total land area.[16]

The British Empire began in 1533 with the Statute of Restraint of Appeals, which

declared “that this realm of England is an Empire”, and took shape with

Elizabeth I’s patent granted to Humphrey Gilbert for overseas exploration,

followed by the establishment of the East India Company, chartered under Queen

Elizabeth I on December 31, 1600, and the Virginia Company, chartered under

James I on April 10, 1606. The Empire grew and expanded, with some setbacks,

such as the American Revolutionary War (or ‘War of Independence’), until 1921,

when the Anglo-Irish War ended. This led to Irish independence, followed by the

1926 Imperial Conference, resulting in the Balfour Declaration, which declared

that all the autonomous communities within the Empire, e.g. the settler

colonies, were equal in status, leading to the creation of the British

Commonwealth. The British Empire formally ended when Zimbabwe was granted

independence on April 18, 1980. It is 1914, however, that brought the end of La

Belle Époque in Europe, marking the end of the era which we have described

above, coinciding with the Federal Reserve Act of December 23, 1913. This piece

of legislation, signed into law by President Woodrow Wilson, established the

Federal Reserve System, which was authorised to issue Federal Reserve Notes as

legal tender (commonly called United States Dollars).[17]

The Age of Fiat Currency

While the Romans introduced

massive currency debasement and inflation, it was the Chinese who pioneered

true fiat currency, which consisted of paper banknotes with no value other than

the value decreed by government fiat. Fiat currency is, by its nature, not money.

While it has some value, and it is portable and fungible, it is not scarce,

because it can constantly be printed/expanded, and it is not durable, since it

consists of either electronic digits in a bank ledger or notes of paper which

do not last. History bears this out. All fiat currencies have, throughout

history, gone to zero and no longer hold any nominal value. [18]

Those Chinese banknotes from the Yuan and Ming Dynasties? They are now worth

nothing at all and are only of interest to collectors or historians.

Confederate banknotes? Worthless. Continental dollars? Useless. Bronze and

copper coins? Useless. None of these are of any interest, except to collectors.

If that is the case, why should any fiat currency have value now? The value of

existing fiat currencies is dependent on three main factors: belief in the

value of the currency, the authority of the government behind the currency, and

the rate of inflation. If people are told by the government that a piece of

paper has value, they believe that it has value. The government then backs up

this belief through force of arms. It punishes forgers, and it recognises the

currency as legal tender. It sends its money abroad and backs it up with

military force. People who steal it are punished, as are those who misuse the

currency. Authority backs up fiat. Third, the more currency that is printed and

enters circulation, and the higher the velocity of currency (i.e. how fast

currency circulates), the greater the rate of inflation. This type of inflation

results, according to Investopedia, from expansionary monetary policy, which

creates a surplus of liquidity, bringing down the value of money in relation to

the price of goods.[19]

How then did fiat currencies

become the norm across the globe? China’s various experiments with paper

currency led to hyperinflation and had to be replaced by a silver standard.

Paper did not originally exist in the West, which used sheepskin (vellum),

papyrus and other materials for books. The earliest examples of papermaking can

be traced to the 2nd century BCE in China, with its invention being

attributed to Cai Lun, an imperial eunuch official of the Han Dynasty.[20]

Paper was probably brought to Europe via al-Andalus, with the earliest example

of paper dating to the 11th century. Papermaking began in Europe in

Toledo, and it reached England by 1490.[21]

Europeans first learned of Chinese paper currency from early travellers, such

as the Venetian merchant and explorer, Marco Polo, and the Flemish missionary

and explorer, William of Rubruck. Marco Polo recorded his observations in a

chapter of his book of travels entitled "How the Great Kaan Causeth the

Bark of Trees, Made Into Something Like Paper, to Pass for Money All Over his

Country”.[22]

Insecurity in medieval Italy and Flanders led to the creation of promissory

notes, which were used to avoid transporting large sums of money over long

distances. These promissory notes may be regarded as early bills of exchange or

cheques. By the 14th century, these notes, called ‘banknotes’ or nota

di banco, with the Italian word banco meaning ‘bench, counter’, derived

from the desks or exchange counters used by Renaissance Jewish Florentine

bankers, who made transactions on desks with green tablecloths.[23]

International payments were made using a bill of exchange (Italian lettera

di cambio), which was a promissory note backed by a ‘virtual currency

account’, with physical currencies being related to the virtual currency.[24]

This avoided the actual movement of precious metals over long distances.

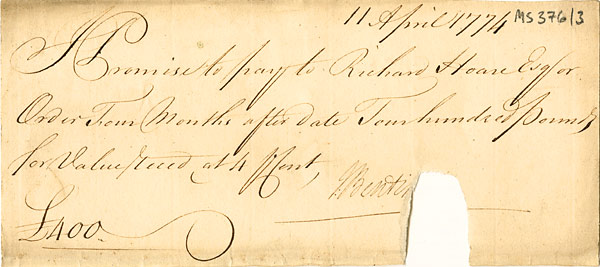

These early promissory notes

were not money or currency in themselves, but, rather, promises to pay a

certain amount of money. It was only in the mid-17th century that

banknotes became a means of payment in themselves. During that period,

goldsmith-bankers of London began to give out receipts payable to the bearer of

the document rather than the depositor of the gold, meaning that the notes

themselves were tradable and could be exchanged without referring to the original

deposit. These goldsmiths also introduced another innovation—fractional reserve

banking. They began to issue a greater number of banknotes than the total value

of their gold reserves, meaning that there was more currency in circulation

than there were reserves to pay for it.[25]

This has resulted in the absurd scenario where there could be a ‘run on the

banks’, i.e. where people rush to withdraw their precious metals or money and

find out that there isn’t enough money to go around. The first attempt by a

central bank to issue banknotes was in 1661, when Stockholms Banco, the

predecessor of the modern Sveriges Risksbank, issued banknotes which replaced

the copper-plates then used as a means of payment.[26]

Three years later, the bank went bankrupt due to over-printing of banknotes far

beyond the bank’s actual supply of precious metals. Its replacement was the

Riksens Ständers Bank, but the lesson had been learned and this new ‘central

bank’, established in 1668, did not issue any banknotes until the 19th

century.[27]

The first European attempt at central banking and government issued fiat

currency had failed, just as it had under Yuan and Ming-Dynasty China.

|

| Promissory note (1774) |

The development of the first Europe-based fiat currencies and central banks brought with it an accompanying development in insidious economic ideas. The economist Nicholas Barbon, for example, quipped that money was “an imaginary value made by a law for the convenience of exchange.”[29] Barbon here ignores five thousand years of history and conflates money with currency. He would later go on to inspire John Maynard Keynes and other 20th-century economists, who have also regarded manipulation of the economy as a positive social good. Moreover, Barbon advocated the use of paper currency and credit money, and argued that a country’s wealth could be identified with its population, rather than with its stock of precious metals.[30] Adam Smith (1723 – 1790), in contrast, defined the wealth of a nation as its “annual produce” or “the necessaries or conveniences of life which it annually consumes”.[31] According to Blenman (2016), Adam Smith identified several key elements to increasing wealth and bringing about universal prosperity. These he summarises as: (1) enlightened self-interest, (2) limited government, and (3) solid currency tied to a free-market economy.[32] Currency, Smith argued, should be backed by hard metals, which would prevent it from being depreciated in order to pay for wars or other wasteful expenditures, and this would also result in lower taxes, the elimination of tariffs and international free trade.[33] By enlightened self-interest, he meant that it is in the interests of the vendor to ensure that his wares/goods are high-quality, so that he can make a profit, and this goes hand in hand with thrift and hard work. Thrift and saving, indeed, can only go hand in hand with hard money, e.g. gold or silver, and this would allow the individual to save up capital to invest, buy labour-saving machinery or other business-enhancing assets, and encourage innovation which would return invested capital and enhance one’s standard of living, as well as the standard of living for the whole society.[34] Adam Smith did not entirely oppose the use of paper currency, but he did state clearly that the total amount of paper currency circulating within a country should never exceed metallic money.[35]

“I

am fully persuaded that we shall never restore our currency to its equitable

state, but by this preliminary step, or by the total overthrow of our paper

credit.”[36]

-

David Ricardo, The High Price of Bullion

It was in England that

banknotes became a permanent phenomenon with the establishment of the Bank of

England in 1694, created to raise money for funding a war against France. The

bank began issuing notes in 1695 with a promise to pay the bearer the value of

the note on demand. These notes, originally handwritten to a precise amount,

were eventually replaced by fixed denomination notes, with notes ranging from

£20 GBP to £1000 being available by 1745.[37]

Fully-printed banknotes which did not name the payee and did not require a

cashier’s signature did not appear in the UK, however, until 1855.[38]

Nevertheless, all of these notes were actual promises to pay actual amounts of

money. The British pound (pound sterling), which traces its origins to the

Roman libra (approximately 328.9g), has varied in weight throughout time. In

757 AD, one pound consisted of a Tower pound of silver (approximately 350 g),

this being based on the silver penny used by King Offa. Silver pennies were

struck from Arabic dirhams, with one pound weighing 120 Arabic dirhams.[39]

One dirham during the Abbasid Caliphate weighed approximately 2.8 or 2.9 grams

of silver,[40]

while the gold dinar weighed 1 mithqal (4.25 grams) of gold.[41]

Under Henry VIII, the pound sterling was changed to the Troy pound, i.e. 12

troy ounces or 373.241 grams.[42]

In 1717, Sir Isaac Newton, who was then Master of the Mint, set the price of

gold at £4.25 GBP, essentially establishing a gold standard that was to last for

several centuries.[43]

In 1816, the gold standard was officially established, and, in 1817, the

sovereign was introduced—a gold coin valued at 20 shillings.[44]

Banknotes during this period, therefore, did not replace the gold standard, and

they served as promissory notes which could be redeemed for gold (or the

equivalent value in silver).

The Bank of England, which

is the 8th oldest bank in the world, became the template for future

central banks. What is a central bank? A central bank is an institution which

manages a nation’s currency, money supply and interest rates.[45]

This runs counter to the free market idea that the value of sound money should

be determined by the market, not by governments. Central banks, therefore, are

incapable of issuing or creating sound money, but they are able to determine

and issue legal tender, i.e. the nationally-authorised and recognised currency.

As already mentioned, in North America in the 18th century, the

Spanish dollar, a fine silver coin, was widespread, and formed the basis for

later ‘dollars’. Following the existing practise of using promissory notes,

paper currency was widespread in the early British colonies, and this was

regulated by the British Parliament through the Currency Acts of 1751, 1764 and

1773.[46]

During the American Revolution, however, the thirteen colonies became

independent states and could issue paper currency to fund their military

expenditures. The Continental Congress, also, which was formed from representatives

from each colony/state, began to issue paper currency called Continental

dollars. Due to overprinting, however, the currency depreciated rapidly, and,

by the end of the war, it was practically worthless, just like every other fiat

currency experiment in the centuries which preceded it. In addition to paper

currency, there was also commodity money, e.g. tobacco, beaver skins, and

wampum, and specie (coins) (such as the Spanish dollar). Paper currency was

divided into promissory notes and bills of exchange—the latter being fiat

currency which could not be exchanged for gold or silver.[47]

The Continental Congress issued some $241,552,780, which quickly fell to almost

zero value (being worth 1/40th of their face value by 1780), giving

rise to the phrase “not worth a continental.”[48]

|

| One-third of a Continental dollar |

After the ratification of

the United States Constitution, the Federal Government decreed that Continental

dollars could be exchanged for treasury bonds at 1% of their face value.[50]

That’s a 99% decrease in value, indicating, yet again, that all fiat currencies

eventually go to zero.[51]

Nowadays, a Continental dollar has nothing but collector’s value. The United

States Constitution also sought to do away with the concept of fiat currency

altogether, decreeing that Congress had the power “to borrow money on the

credit of the United States” and “to coin Money, regulate the Value thereof,

and of foreign Coin, and fix the Standard of Weights and Measures”, but it did

not give Congress the power to create fiat currency or bills of exchange.[52]

Rather, Congress had the power to coin money from precious metals. This is

reinforced by Article I, Section X, which states that “No State shall… coin

Money; emit Bills of Credit; make any Thing but gold and silver Coin a Tender

in Payment of Debts.”[53]

This blocked states both from coining their own money and from creating fiat

bills of credit, as well as from paying debts in anything but gold and silver

coinage. Despite this fact, fiat currency is now widely used by state

governments within the United States, and this article of the Constitution is

widely ignored. The framers of the Constitution were determined to avoid the

hyperinflation which had beset the Continental dollar and other state

currencies during the Revolutionary War, but their wise determinations have now

fallen on deaf ears. In the 1790s, Alexander Hamilton, Secretary of the

Treasury, argued for the creation of a national bank, which was opposed by the

Jeffersonian Republicans. This led to the creation of the First Bank of the

United States, based in Philadelphia, Pennsylania, which was dissolved in 1811

when its charter expired.[54]

It was succeeded by the Second Bank of the United States in 1816, also based in

Philadelphia, which had a 20-year charter, expiring in 1836, after which it

became a private corporation, before being liquidated in 1841.[55]

Following this, there was no central bank in the United States until the

Federal Reserve System was established in 1913.

The American Civil War,

which lasted from 1861 to 1865, split the United States into two rival

nation-states, each of which issued paper currency. The Legal Tender Act of

1862 allowed the issuance of $150 million in national notes called ‘greenbacks’

due to their colour, which were issued without backing by gold and silver, only

the credibility of the United States government.[56]

Additional legal tender acts allowed Congress to issue more and more currency

so that, by the end of the war, more than $447 million USD was in circulation.

Meanwhile, the Confederate States of America, based on the South, issued their

own currency, called the ‘greyback’ to distinguish it from the ‘greenback’.[57]

As in the Revolutionary War, these greybacks were bills of credit and were not

backed by precious metals, leading to eventual hyperinflation. By the time the

war ended, Confederate dollars were not worth the paper they were printed on. Of

course, in the 21st century, greenbacks are also worthless, as

government-backed paper currency has to be continually updated and exchanged

for newer notes. A Spanish dollar from the 19th century, however,

could be exchanged for its value in gold or its collector’s value, and would now

have a significant value. In 1878, the Brand-Allison Act required the

government to purchase $2 - $4 million USD of silver per month at market prices

and coin it into silver dollars. Silver and gold coinage both already existed

within the United States at the time, with the Coinage Act of 1792, which

pegged the value of the United States dollar to the Spanish silver dollar. The

U.S. Mint originally issued gold, silver and copper coins. The U.S. dollar was

a silver coin weighing 24.1 g of pure silver, half dollars weighing 12g of pure

silver, and quarter dollars weighing 6.01 g of pure silver. There were also

three gold coins: Eagles, which were valued at $10.00 and contained 16.04 g of

pure gold, half eagles, valued at $5.00 and containing 8.02 grams of pure gold,

and quarter eagles, valued at $2.50 and containing 4.01 grams of pure gold.

This thus created a bimetallic gold-silver standard.[58]

In 1875, Congress passed the

Specie Payment Resumption Act, which required the Treasury to allow U.S.

banknotes to be redeemed for gold after January 1, 1879, and the bimetallic

standard was abandoned in 1900 with the Gold Standard Act, which defined the

U.S. dollar as 23.22 grains (1.505 g) of gold.[60]

One troy ounce of gold was thus fixed at a value of $20.67. This established a

gold standard within the United States. Nevertheless, silver coins continued to

circulate until 1964, when silver was removed from dimes and quarters and the

half-dollar was debased to contain only 40% silver, the latter of which was

last issued in 1970.[61]

The gold standard faced several setbacks, however, due to the World Wars One

and Two. Executive Order 6102 (1933) under President Franklin D. Roosevelt

ordered that gold coins were to be confiscated, and the price of gold was set

at $35 per troy ounce; this was eventually reduced to $42.22 per troy ounce

before President Nixon abandoned the gold standard on August 15, 1971, allowing

the dollar to become a fully-fiat currency.[62]

This is known as the ‘Nixon shock’, as it ended the Bretton Woods system of

international financial exchange. The Bretton Woods system was established in

1944 with the Bretton Woods Agreement between 44 Allied nations, which fixed

exchange rates between major currencies and pegged them to the United States

dollar and gold.[63]

This resulted in the United States hoarding two-thirds of the world’s gold.

With the Nixon shock, however, most nations also ended their currencies’ peg to

the dollar, leading to widespread inflation and economic aftershocks. 1971

marks the beginning of the current Age of Fiat.

“Paper

is being reduced to its intrinsic value.”[64]

-

Voltaire

Since ending the gold

standard, the unemployment rate in the United States has averaged over 6%,

averaging 8.5% in 1975 and almost 10% in 1982, compared with an average of 5%

during the post-WWII gold standard era, with economic growth averaging 2.9%

compared to 4% under the gold standard.[65]

Kadlec (2011) argues that the U.S. economy today is about $8 trillion USD

smaller than it would have been under a gold standard, and the median family

income is 50% lower than it should have been.[66]

Like Diocletian before him, Nixon combined this currency devaluation with price

controls, freezing wages and prices for 90 days and establishing a 10% tariff

on imports.[67]

The effect on the U.S. dollar was devastating. It plunged by a third in value

during the 1970s, with currency volatility threatening several national economies

since, including Asian and Latin American countries in 1997.[68]

Price controls under Nixon had to be extended until 1974, when Nixon resigned.

They were ineffective, however, in reducing inflation, which had topped 11%.[69]

Not quite as bad as Diocletian, but Rome’s price controls were more rigorous.

Nixon’s economic policies coincided with the Great Inflation, which lasted from

1965 to 1982.[70]

The Great Inflation began in the 1960s, as U.S. dollars were increasingly being

converted into gold—in other words, countries were sending dollars in return

for gold, causing the value of the dollar to slip. When Nixon ended the gold

standard, there was nothing to tether the dollar’s value, so it fluctuated

wildly, further exacerbating inflation. To give some perspective on how much

the dollar has declined in value since being taken off the gold standard, $1.00

in 1971 in now worth about $6.19 in 2018 dollars, with annual inflation during

the period from 1971 to present of over 3.96%.[71]

If you had saved money in the 1970s until now, your currency would have lost more

than 5/6th its value.

Savers, investment guru

Robert Kiyosaki likes to inform us, are losers.[72]

When you save money in your bank account, it loses value because it isn’t

pegged to anything. If one dollar in 1971 is worth $6.19 today, what will your

dollar saved today be worth in 10 years’ time? Not much, likely. One dollar in

1914, when the Federal Reserve was established, is now worth $24.65—that’s with

an average annual inflation from 1914 – 2018 of 3.13%.[73]

It has thus lost 24.65 times its value over that period. If we take 1792 as the

beginning of the United States dollar, with the Coinage Act of 1792, what would

the value of a 1792 dollar be today? The answer: $25.53 in 2017 dollars, and

that is with an inflation rate of only 1.45% over the time period 1792 – 2017.[74]

The difference between 1 dollar in 1792 and 1914 is very small, as the dollar

was originally based on precious metals. However, the difference from 1914 to

2018 is huge. Up until 1914, savers were definitely not losers. However, from

1914 to present, and especially from 1971 to present, savers have most

certainly been losers, as the value of the United States dollar—and all fiat

currencies—is in continual decline, just as the value of Roman currency was in

decline at the very end of the Roman Empire in the third and fourth centuries, before

Rome was finally sacked and the last Emperor deposed. We are living in very

similar times. With the end of the gold standard, and the great prosperity that

that standard had brought to mankind, and the reign of central banks and the

Federal Reserve System, what can be done to bring humanity back to sound money

and a solid money system? Moreover, what is the next step in the evolution of

money, and how can people weather the storm of the inevitable fall of empires

certain to come when the current system collapses?

Digital Money and

Computer Banking

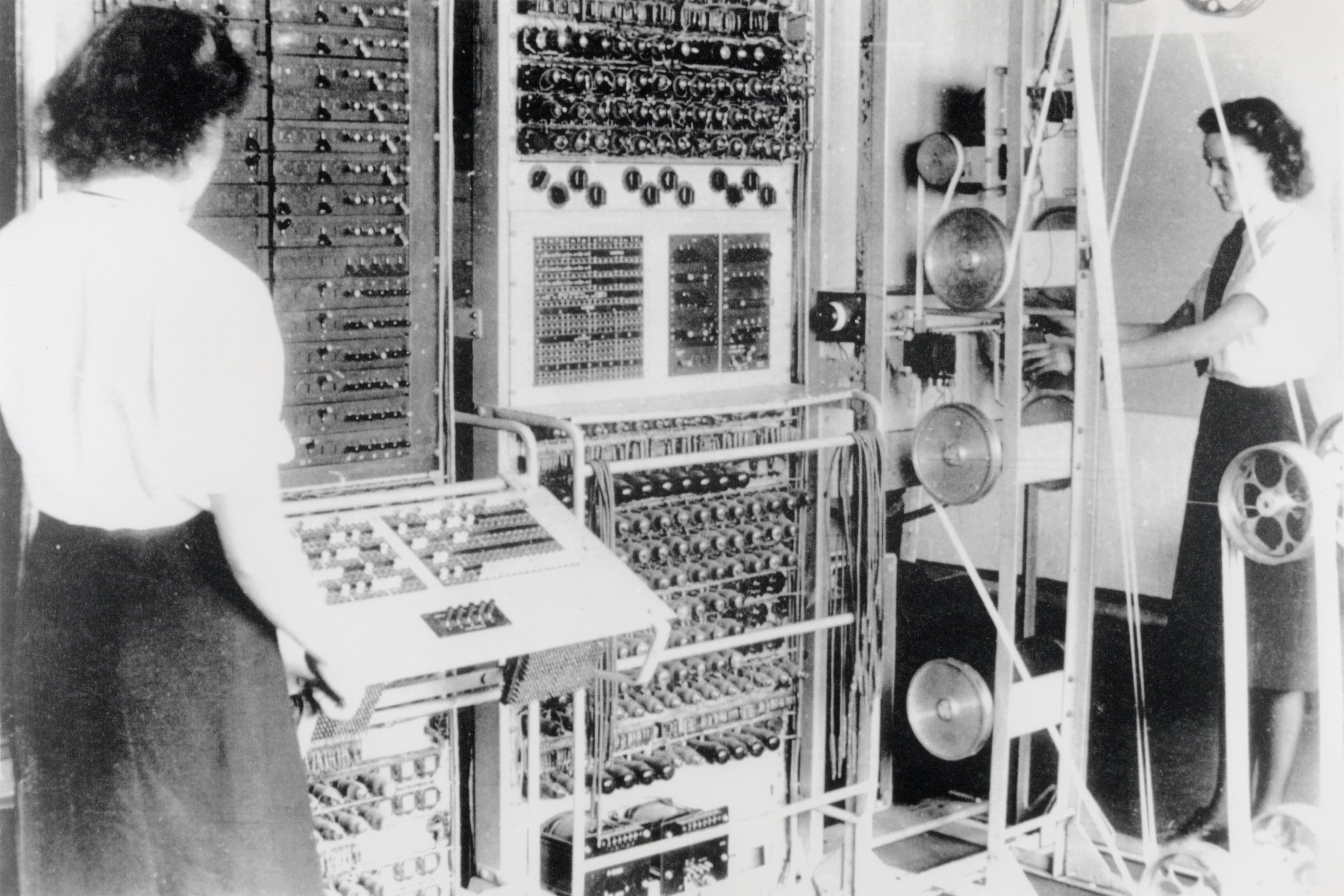

We live in an increasingly

digital age, when digital assets are starting to take the place of physical

assets. Since the invention of the computer, starting with Charles Babbage’s

Analytical Engine invented and improved between 1833 and 1871, followed by the

Z1 programmable computer of Konrad Zuse (invented 1936 – 1938), and the

Colossus (December 1943),[75]

up until modern personal computer, laptops, tablets, smartphones and smart

watches, we have become increasingly dependent on machines for business, trade,

banking and payment systems. Computers were originally of interest to

governments, the military and scientists, who used them to crack codes and

perform high-speed calculations. By 1954, however, the banking industry got in

on the new technology. A partnership between Bank of America and the Stanford

Research Institute resulted, in 1954, in the creation of the Remington Rand UNIVAC-1,

the world’s first computer designed for business use, which was a massive

computer utilising vacuum tubes and magnetic tapes to operate, processing

12,000 numbers or letters per second.[76]

This was followed, in September 1955, by the creation of ERMA—the Electronic

Recording Method of Accounting, which could process 33,000 accounts in the time

it would take a bookkeeper to do 245, posting accounts, identifying stop

payments and holds, flagging overdrafts, storing account information, printing

daily and monthly bank statements, and sorting 600 cheques per minute—a

reduction in time of 80%.[77]

From that time forward, banking and money would no longer be a paper affair—we

had entered a new, digital age of banking—an age of digital ledgers and

computer-based transactions. This was a departure as radical as the Chinese

invention of paper currency.

|

| Colossus codebreaker |

What most people do not

realise is that our currency has become almost completely digital. When people

think of U.S. dollars, Euros, Great British pounds, etc. they think of printed

notes and coins. Somewhere in our imagination, there is a huge vault at the

back of our local bank, where all of our money is stored in neat piles of cash.

If the bank isn’t careful, an old robber, like Jesse James, might swing buy,

hold everyone hostage and loot the bank, taking our money with him. This, of

course, is not the case. There is no vault at the back of the bank with all

your money in it, because your cash doesn’t really exist at all. It’s all just

1s and 0s in and computer ledger. The New Yorker estimates that there is about

$1.4 trillion U.S. dollars in circulation, with the amount tripling over the

last two decades (2001 – 2016)—that’s an immense amount of cash.[79]

They estimate that the average American carries about $30 dollars, with 1/20th

having a stash of about $1200 at home, and everyone else averaging about $74.[80]

Of the $1.5 trillion U.S. dollars in circulation, 80% of this is comprised of

11.5 billion $100 notes, with, each year, 70% of new bills being used to replaced

older notes which are going out of circulation.[81]

The total money supply (called M2) in the United States, however, is much, much

bigger than this—in fact, it amounts to around $14 trillion USD, with physical

currency making up only 11% of the total value. That means that digital cash

makes up 89% of the U.S. money supply.[82]

We do not have to imagine a world where digital currency is the norm, because

it already exists. We already live in a world where the vast majority of our

currency is digital, and physical notes and coins are only a tiny fraction of

that total amount. Worldwide, in fact, only 8% of the world’s currency exists

as physical cash, with 92% consisting of digital money![83]

Even if everyone wanted to convert their digital cash into physical notes and

coins, they would be unable to do so, as such an amount of physical currency

simply does not exist! What does that mean for us today? It means, essentially,

that all the dollars, euros, pounds and other currency that you have in your

bank account, exists as nothing more than digital ones and zeros in a digital

ledger which exists within a computer database. If that ledger, or that

computer database, were destroyed, your “money” would cease to exist. It also

means that your “money” can be hacked, stolen or confiscated via computers or

the internet.

This is a shocking

revelation to most people, who like to believe that governments “print” or

“coin” money. That used to be the case, but no longer. Physical cash still

exists, but more as a mask or illusion to make us feel like fiat currencies

have real value. The value of a fiat currency, in fact, is only what we believe

it to have. As with the 17th century economist, Nicholas Barbon, the

modern banking system is based on the idea that money is “an imaginary value

made by a law for the convenience of exchange.”[84]

This is wrong, of course, as fiat currency is not, strictly speaking, money but

currency, but the point still applies—U.S. dollars, euros, British pound

sterling, Chinese renminbi, etc. all exist as mere abstractions. The entire

banking system is a mere façade which hides the reality that currency is merely

a collection of numbers stored and moved from one computer to another on a

network, with the total amount of these numbers constantly being increased—indeed,

on a massive scale—by governments, who use this increase to reduce the

purchasing power of citizens, while allowing themselves to create more debt,

pay off existing debts, and fund ever-expansive spending programmes, including

“quantitative easing”, military spending and entitlements. This digital age of

currency was further supported by the creation of non-physical methods of

payment, including the credit card, which was invented by Frank McNamara in

1950, when the Diners Club card was released.[85]

This was followed by American Express and Visa (originally BankAmerica) in

1958, and eventually by MasterCard, Discover Card and JCB.[86]

With the dawn of the credit

card, and later debit card, people no longer needed to rely on physical cash

for payments. Banknotes and coins have, throughout the late 20th and

early 21st centuries, been rendered almost entirely obsolete. Credit

cards, have, in addition, not only facilitated payments, but also allowed

Americans and people from all over the world, to amass staggering amounts of

personal debt, as people often end up spending more money than they actually

have. Other methods of digital payment have also arisen, including PayPal,

which was launched in 1999, allowing for easy digital transactions between

individuals across the planet. PayPal, however, still relied on existing

banking systems and fiat currency. Most people, during the late 20th

century, accepted that this would always be the case—that we would always be

reliant on the banking system and government-created currency. To say otherwise

would be anarchist, antinomian or utopian. Indeed, while communists and

Marxists dreamed of a world where money no longer needed to exist—on the one

hand, libertarians dreamed of a world in which everyone could make their own

currency, while gold-bugs and silver-bugs hoped for an eventual reinstatement

of the gold standard, or a bimetallic standard. All of these ideas remained

within the realm of speculation and fantasy, however, until two new

developments began to take shape: developments in digital cryptography, and a

wide expansion in the number of people using personal computers and the

internet. The World Wide Web, invented by English scientist Sir Tim Berners-Lee

(b. 1955), was launched in 1989, and the idea of creating a new, encrypted digital

currency began to take shape. My next article/chapter, will outline the rise of

Bitcoin, the world’s newest form of sound money, which is that new digital

currency, and which has now come to be regarded as a secure store of value and a

medium of exchange.

©️NJ Bridgewater 2018

SOURCES:

Authorised Version of the

Bible (King James Bible / KJV) (1611) The Holy Bible, Conteyning the

Old Testament, and the New: Newly Translated out of the Originall tongue Newly

Translated out of the Originall tongues: & with the former Translations

diligently compared and reuised (London: Robert Barker). Available

online at: http://biblehub.com/kjv/ ; https://www.biblegateway.com/keyword/ ;

https://quod.lib.umich.edu/k/kjv/simple.html ;

https://archive.org/details/1611TheAuthorizedKingJamesBible ;

http://www.sacred-texts.com/bib/kjv/index.htm ; https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/10

(accessed 18/07/2018)

ADANA (Anadolu Agency)

(2014) Money used by Sumerians in Mesopotamia, says expert, Hurriyet Daily

News, January 13, 2014 00:01:00. URL:

http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/money-used-by-sumerians-in-mesopotamia-says-expert-60909

(accessed 12/11/2018)

Bank of America

Corporation (2018) Bank of America revolutionizes banking industry, Bank of

America Corporation. URL: https://about.bankofamerica.com/en-us/our-story/bank-of-america-revolutionizes-industry.html#fbid=k9IDxSLJ4_R

(accessed 21/11/2018)

Nicholas Barbon, Discourse

On Trade, 1690. p.37. URL:

https://archive.org/details/nicholasbarbonon00barb (accessed 21/10/2018)

Bruce Bartlett (1994)

How Excessive Government Killed Ancient Rome, Cato Journal, Vol. 14, No.

2, 1994, p. 299. URL:

https://object.cato.org/sites/cato.org/files/serials/files/cato-journal/1994/11/cj14n2-7.pdf

(accessed 15/11/2018 11:35 AST)

Joy Blenman (2016) Adam

Smith and "The Wealth Of Nations". Investopedia, September 7,

2016 4:53 PM EDT. URL: https://www.investopedia.com/updates/adam-smith-wealth-of-nations/

(accessed 19/11/2018)

Andrew Boyd (2018) Who

invented credit cards, Credit Card Compare, July 4, 2018. URL:

https://www.creditcardcompare.com.au/blog/who-invented-credit-cards/ (accessed

21/11/2018)

NJ Bridgewater (2017) Gold:

10 Ways to Make Money Using Gold (Abergavenny: Jaha Publishing)

NJ Bridgewater (2017)

What is Bitcoin? Crossing the Bridge, 7 December 2017. URL: https://nicholasjames19.blogspot.com/2017/12/what-is-bitcoin.html

(accessed 23/11/2018)

NJ Bridgewater (2018)

The Origins of Wealth (Part 1 of 4), Crossing the Bridge, Thursday, 5,

July 2018. URL: https://nicholasjames19.blogspot.com/2018/07/the-origins-of-wealth-part-1-of-4.html

(accessed 02/11/2018)

Brilliant Maps (2015)

Roman Empire GDP Per Capita Map Shows That Romans Were Poorer Than Any Country

in 2015, BrilliantMaps.com, May 4, 2015. URL: https://brilliantmaps.com/roman-empire-gdp/

(accessed 14/11/2018)

Michael Bryan (2013)

The Great Inflation, Federal Reserve History, November 22, 2013. URL:

https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/great_inflation (accessed

20/11/2018)

Edwin Cannan (1922) Wealth:

A Brief Explanation of the Causes of Economic Wealth (London: P.S. King and

Son, 1922). URL: https://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/2063 (accessed 19/11/2018

13:49 AST)

Computer Hope (2018)

When was the first computer invented? Computer Hope, 11/13/2018. URL:

https://www.computerhope.com/issues/ch000984.htm (accessed 21/11/2018)

CPI Inflation

Calculator (2018) $1 in 1792 → 2017 | Inflation Calculator.” U.S. Official

Inflation Data, Alioth Finance, 20 Nov. 2018. URL: https://www.officialdata.org/1792-dollars-in-2017?amount=1 (accessed 20/11/2018)

Jason Daley (2018)

People Lived in This Cave for 78,000 Years, Smithsonian.com, May 11,

2018. URL:

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/people-lived-cave-78000-years-180969051/

(accessed 22/11/2018)

Jeff Desjardins (2018)

Here's how much US currency there is in circulation, Business Insider,

19.04.2018, 01:30. URL: https://www.businessinsider.de/heres-how-much-us-currency-there-is-in-circulation-2018-4?r=US&IR=T

(accessed 21/11/2018)

Tyler Durden (2018)

Fiat Currency Always Ends In Collapse, ZeroHedge, Mon, 06/18/2018 –

20:55. URL: https://www.zerohedge.com/news/2018-06-18/fiat-currency-always-ends-collapse

(accessed 21/11/2018)

The Economist (2010)

Tricky Dick and the dollar, The Economist, Mar 25th 2010.

URL:

https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2010/03/25/tricky-dick-and-the-dollar

(accessed 20/11/2018)

Peter Foldvari &

Bas van Leeuwen (2010) Comparing per capita income in the Hellenistic world:

the case of Mesopotamia, 5 July 2010. URL:

http://www.basvanleeuwen.net/bestanden/Mesopotamia%20GDP%201Julyl2010.pdf

(accessed 14/11/2018)

Dominic Frisby (2017)

What wages in ancient Athens can tell us about the silver price today, MoneyWeek,

02/03/2017. URL: https://moneyweek.com/462534/what-wages-in-ancient-athens-can-tell-us-about-the-silver-price-today/

(accessed 12/11/2018)

Mark Gimein (2016) Why

Digital Money Hasn’t Killed Cash, The New Yorker, April 28, 2016. URL:

https://www.newyorker.com/business/currency/why-digital-money-hasnt-killed-cash

(accessed 21/11/2018)

Global Security

(2000-2018) How Much is That in Real Money? GlobalSecurity.org. URL:

https://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/spqr/money-1.htm (accessed

12/11/2018)

Zachary A. Goldfarb

(2014) Who was the richest man in all of history? The Washington Post,

April 1, 2014. URL:

https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2014/02/19/who-was-the-richest-man-in-all-of-history/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.b706e1e51b0d

(accessed 13/11/2018)

Ed Grabianowski (2018)

How Currency Works, HowStuffWorks.com. URL:

https://money.howstuffworks.com/currency6.htm (accessed 21/11/2018)

H Brothers Inc

(2007-2018) Calculate the value of $1.00 in 1971, DollarTimes,

20/11/2018. URL: https://www.dollartimes.com/inflation/inflation.php?amount=1&year=1971

(accessed 20/11/2018)

Tim Harford (2017) How

the world's first accountants counted on cuneiform, BBC News, 12 June

2017. URL: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-39870485 (accessed 12/11/2018)

Henry Hazlitt (1971)

Poor Relief in Ancient Rome, Foundation for Economic Education (FEE),

originally published Thursday, April 01, 1971. URL:

https://fee.org/articles/poor-relief-in-ancient-rome/ (accessed 14/11/2018)

Stefan Heidemann

(2011) The early Islamic Empire and its religion on coin imagery. In Albrecht

Fuess, Jan-Peter Hartung (editors) (2011) Court Cultures in the Muslim

World: Seventh to nineteenth centuries (London; New York: Routledge). URL:

https://www.aai.uni-hamburg.de/voror/personen/heidemann/medien/2011-heidemann-courtcultures2011-representation.pdf

(accessed 19/11/2018)

Jacob H. Hollander

(1911) The Development of the Theory of Money from Adam Smith to David Ricardo,

The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 25, No. 3 (May, 1911), pp.

429-470 (42 pages). URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1883613 (accessed

19/11/2018)

Investopedia (2018)

What causes inflation, and does anyone gain from it? Investopedia, LLC,

updated January 22, 2018 1:05 PM EST. URL:

https://www.investopedia.com/ask/answers/111314/what-causes-inflation-and-does-anyone-gain-it.asp

(accessed 19/11/2018)

JM Bullion (2015) How

Much Fine Silver Bullion is in the World? JM Bullion. URL:

https://www.jmbullion.com/investing-guide/types-physical-metals/how-much-fine-silver-bullion-in-world/

(accessed 11/12/2018)

Charles Kadlec (2011)

Nixon's Colossal Monetary Error: The Verdict 40 Years Later, Forbes, Aug

15, 2011, 10:00am. URL: https://www.forbes.com/sites/charleskadlec/2011/08/15/nixons-colossal-monetary-error-the-verdict-40-years-later/#558a84ff69f7

(accessed 20/11/2018)

Robert Kiyosaki (2005)

Why Savers are Losers, RichDad.com, Monday, October 17, 2005. URL:

http://www.richdad.com/Resources/Articles/why-savers-are-losers.aspx (accessed

21/11/2018)

Julia Limitone (2017)

Bitcoin is more powerful than physical money: Overstock CEO, Fox Business,

published November 20, 2017. URL:

https://www.foxbusiness.com/features/bitcoin-is-more-powerful-than-physical-money-overstock-ceo

(accessed 21/11/2018)

Mike Maloney (2015) Guide

to Investing in Gold & Silver: Protect Your Financial Future (Scottsdale,

Arizona: RDA Press LLC), p. 217. Download the free PDF from: https://goldsilver.com/promo/freebook/

(accessed 25/11/2018)

Mark (2012) Tales From

Herodotus XIV. Two Stories of the Alcmaeonid Family (translation), posted on

August 17, 2012. URL:

https://metaphrastes.wordpress.com/2012/08/17/tales-from-herodotus-xiv-two-stories-of-the-alcmaeonid-family/

(accessed 13/11/2018)

Mary Ames Mitchell

(2015) Fifteenth Century Portuguese Dinheiro [Money], Crossing the Ocean Sea.

URL: http://www.crossingtheoceansea.com/OceanSeaPages/OS-46-Dinheiro.html

(accessed 16/11/2018)

John Morley (1872), In

The Quarterly Review, Vol. 135, July & October, 1873 (London: John

Murray)

Robert Nedelkoff

(2011) Forty Years After The “Nixon Shock”, The Nixon Foundation, August

5, 2011. URL:

https://www.nixonfoundation.org/2011/08/forty-years-after-the-nixon-shock/

(accessed 20/11/2018)

Chris Parker (2016) A

short history of the British pound, World Economic Forum, 27 Jun 2016.

URL:

https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/06/a-short-history-of-the-british-pound/

(accessed 19/11/2018)

Joseph R. Peden (2017)

Inflation and the Fall of the Roman Empire, Mises Daily Articles,

10/19/2017. URL: https://mises.org/library/inflation-and-fall-roman-empire

(accessed 14/11/2018)

Lawrence W. Reed

(1979) The Fall of Rome and Modern Parallels, Foundation for Economic

Education (FEE), originally published Thursday, April 21, 1979. URL:

https://fee.org/articles/poor-relief-in-ancient-rome/ (accessed 14/11/2018)

David Ricardo (1810) The

High Price of Bullion: A Proof of the Depreciation of Bank Notes (London:

John Murray), p. 44. URL: https://archive.org/details/highpriceofbulli10rica/page/n5

(accessed 21/11/2018)

Walter Scheidel (2009)

Rome and China: Comparative Perspectives on Ancient World Empires

(Oxford: Oxford University Press)

Silver Prices Today,

Live Spot Prices & Historical Charts, Money Metals Exchange. URL:

https://www.moneymetals.com/precious-metals-charts/silver-price (accessed

12/11/2018 07:59 AST)

Thomas Sowell (2004) A

taxing experience, Townhall.com, Nov 25, 2004 12:00 AM. URL:

https://townhall.com/columnists/thomassowell/2004/11/25/a-taxing-experience-n935368

(accessed 14/11/2018)

Thomas Sowell (2010) The

Thomas Sowell Reader (New York, NY: Basic Books)

Spiros (2012) How much

expensive was life in ancient Greece, Hellenic History Subjects,

Saturday, April 7, 2012. URL: https://akrokorinthos.blogspot.com/2012/04/how-much-expensive-was-life-in-ancient.html

(accessed 11/12/2018)

Blair Sullivan,

Geoffrey Symcox (2005) Christopher Columbus and the Enterprise of the

Indies: A Brief History with Documents (Boston, Mass. : Bedford/ St

Martin's)

Nick Szabo (2002)

Shelling Out: The Origins of Money, Satoshi Nakamoto Institute. URL:

https://nakamotoinstitute.org/shelling-out/ (accessed 02/11/2018)

U.S. Constitution, Article I, Section VIII. URL:

https://www.usconstitution.net/xconst_A1Sec8.html (accessed 20/11/2018)

Richard Henry

Timberlake, Kevin Dowd (2017) Money and

the Nation State: The Financial Revolution, Government and the World Monetary

System (London: Taylor and Francis)

Christopher Weber

(2018) A Short History of International Currencies, Weber Global Opportunities p. 3. URL:

http://www.weberglobal.net/Historyofmoneycompleter.pdf (accessed 20/11/2018)

Louis C. West (1916)

The Cost of Living in Roman Egypt, Classical Philology, Vol. 11, No. 3

(Jul., 1916), pp. 293-314 (22 pages). URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/261854

(accessed 11/12/2018)

World Gold Council

(WGC) (2017) How much gold has been mined? World Gold Council. URL:

https://www.gold.org/about-gold/gold-supply/gold-mining/how-much-gold (accessed

12/11/2018)

Zheng Xueyi, Yaguang

Zhang, John Whalley (2010) Monetary Theory from a Chinese Historical

Perspective, National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 16092,

June 2010. URL: https://www.nber.org/papers/w16092.pdf (accessed 15/11/2018)

Jay Zawatsky (2012)

The Collapse of the Fiat System, The National Interest, March 15, 2012.

URL: https://nationalinterest.org/commentary/the-collapse-the-fiat-system-6639

(accessed 21/11/2018)

Wikipedia Articles

Achaemenid coinage (Wikipedia

article). URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Achaemenid_coinage (accessed

12/11/2018 11:33 AST)

Achaemenid Empire (Wikipedia

article). URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Achaemenid_Empire (accessed

12/11/2018 12:24 PM AST)

Ancient Chinese

coinage (Wikipedia article). URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Achaemenid_coinage

(accessed 12/11/2018 11:40 AST)

Ancient Greek Coinage

(Wikipedia article). URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coin (accessed

12/11/2018 07:59 AST)

Bank (Wikipedia article).

URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bank (accessed 19/11/2018 12:10 PM AST)

Banknote (Wikipedia

article). URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Banknote (accessed 19/11/2018)

Bretton Woods system (Wikipedia

article). URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bretton_Woods_system (accessed

20/11/2018 09:58 AST)

British Empire (Wikipedia

article). URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/British_Empire (accessed

19/11/2018 16:48 AST)

Bullion (Wikipedia

article). URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bullion (accessed 12/11/2018 07:45

AST)

Byzantine Empire (Wikipedia

article). URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Byzantine_Empire (accessed

15/11/2018 11:35 AST)

Central bank (Wikipedia

article). URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Central_bank (accessed 20/11/2018

06:59 AST)

Chao (currency) (Wikipedia

article). URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chao_(currency) (accessed

15/11/2018 12:24 PM AST)

Code of Ur-Nammu (Wikipedia

article). URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Code_of_Ur-Nammu (accessed

12/11/2018 08:05 AST)

Coin (Wikipedia article).

URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coin (accessed 12/11/2018 07:49 AST)

Coinage Act of 1792 (Wikipedia

article). URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coinage_Act_of_1792 (accessed

20/11/2018 09:44 AST)

Confederate States

dollar (Wikipedia article). URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Confederate_States_dollar

(accessed 20/11/2018 07:34 AST)

Croesus (Wikipedia article).

URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Croesus (accessed 12/11/2018 08:12 AST)

Denarius (Wikipedia

article). URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Denarius (accessed 12/11/2018

12:03 PM)

Diocletian (Wikipedia

article). URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diocletian (accessed 14/11/2018

12:22 PM AST)

Dirham (Wikipedia article).

URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dirham (accessed 19/11/2018 14:40 AST)

Ducat (Wikipedia article).

URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ducat (accessed 16/11/2018 16:33 AST)

Early American

Currency (Wikipedia article). URL:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Early_American_currency (accessed 20/11/2018

07:03 AST)

Edict on Maximum

Prices (Wikipedia article). URL:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edict_on_Maximum_Prices (accessed 14/11/2018

12:08 PM AST)

End of Roman rule in

Britain (Wikipedia article). URL:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/End_of_Roman_rule_in_Britain (accessed 15/11/2018

12:00 PM AST)

Federal Reserve Act (Wikipedia

article). URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Federal_Reserve_Act (accessed

19/11/2018 17:02 AST)

First Bank of the

United States (Wikipedia article). URL:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/First_Bank_of_the_United_States (accessed 20/11/2018

07:26 AST)

Gold dinar (Wikipedia

article). URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gold_dinar (accessed

19/11/2018 14:43 AST)

Gold reserve

(Wikipedia article). URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gold_reserve (accessed

12/11/2018 11:43 AST)

Guilder (Wikipedia article);

also see: Spanish peseta (Wikipedia article). URL:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guilder (accessed 16/11/2018 15:49 PM AST)

Guldengroschen (Wikipedia

article). URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guldengroschen (accessed

16/11/2018 15:50 AST)

Han dynasty (Wikipedia

article). URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Han_dynasty (accessed

12/11/2018 12:27 PM AST)

Hard currency (Wikipedia

article). URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hard_currency (accessed 02/11/2018

12:02 PM)

History of Chinese currency

(Wikipedia article). URL:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Chinese_currency (accessed 15/11/2018

12:25 PM AST)

History of paper (Wikipedia

article). URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_paper (accessed

19/11/2018 12:02 PM AST)

Kreuzer (Wikipedia article).

URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kreuzer (accessed 16/11/2018 15:50 AST)

List of largest

empires (Wikipedia article). URL:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_largest_empires (accessed 12/11/2018

12:22 PM AST)

Ming Dynasty (Wikipedia

article). URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ming_dynasty (accessed

16/11/2018 14:48 PM AST)

National Bank Act (Wikipedia

article). URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/National_Bank_Act (accessed

20/11/2018 07:32 AST)

Nicholas Barbon (Wikipedia

article). URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nicholas_Barbon (accessed

19/11/2018 13:49 AST)

Odoacer (Wikipedia

article). URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Odoacer (accessed 15/11/2018 12:08

PM AST)

Portuguese dinheiro (Wikipedia

article). URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Portuguese_dinheiro (accessed

16/11/2018 16:20 AST)

Portuguese real (Wikipedia

article). URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Portuguese_real (accessed

16/11/2018 15:59 AST)

Pound (mass) (Wikipedia

article). URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pound_(mass) (accessed

19/11/2018 14:46 AST)

Pound sterling (Wikipedia

article). URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pound_sterling (accessed

19/11/2016 14:57 AST)

Prince Henry the

Navigator (Wikipedia article). URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prince_Henry_the_Navigator

(accessed 16/11/2018 15:31 PM AST)

Qin (state) (Wikipedia

article). URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Qin_(state) (accessed

12/11/2018 11:45 AST)

Reconquista (Wikipedia

article). URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reconquista (accessed

16/11/2018 15:35 PM AST)

Renminbi (Wikipedia

article). URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Renminbi (accessed 19/11/2018

11:06 AST)

Roman currency (Wikipedia

article). URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_currency (accessed

14/11/2018 11:39 AST)

Roman Empire (Wikipedia

article). URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_Empire (accessed

14/11/2018 07:32 AST)

Second Bank of the

United States (Wikipedia article). URL:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Second_Bank_of_the_United_States (accessed 20/11/2018

07:27 AST)

Senate of the Roman

Empire (Wikipedia article). URL:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Senate_of_the_Roman_Empire (accessed 14/11/2018

07:32 AST)

Silver standard (Wikipedia

article). URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Silver_standard#China

(accessed 19/11/2018 11:03 AST)

Spanish dollar (Wikipedia

article). URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spanish_dollar (accessed

16/11/2018 15:06 PM AST)

Spanish peseta (Wikipedia

article). URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spanish_peseta (accessed 16/11/2018

15:43 PM AST)

Tael (Wikipedia article).

URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tael (accessed 19/11/2018 10:56 AST)

Thaler (Wikipedia article).

URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thaler (accessed 16/11/2018 15:56 AST)

United States dollar (Wikipedia

article). URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_dollar (accessed

20/11/2018 09:49 AST)

Wu Zhu (Wikipedia article).

URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Qin_(state) (accessed 12/11/2018 12:01 PM

AST)

[1] See: Prince Henry the Navigator (Wikipedia

article). URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prince_Henry_the_Navigator

(accessed 16/11/2018 15:31 PM AST).

[2] See: Prince Henry the Navigator (Wikipedia

article).

[3] See: Reconquista (Wikipedia article).

URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reconquista (accessed 16/11/2018 15:35 PM AST).

[4] Image source: Silver peso of Philip

V. (a.k.a. Spanish dollar). Mexico mint. Dated 1739 Mº (Mexico monogram).

Public domain. URL:

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/c/c1/Philip_V_Coin_silver%2C_8_Reales_Mexico.jpg

(accessed 22/11/2018).

[5] See: Spanish dollar (Wikipedia article);

also see: Spanish peseta (Wikipedia article). URL:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spanish_peseta (accessed 16/11/2018 15:43 PM

AST).

[6] The Dutch guilder weighed 10.61g and

was a .910 silver coin. See: Guilder (Wikipedia article); also see:

Spanish peseta (Wikipedia article). URL:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guilder (accessed 16/11/2018 15:49 PM AST). See

also: Guldengroschen (Wikipedia article). URL:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guldengroschen (accessed 16/11/2018 15:50 AST);

Kreuzer (Wikipedia article). URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kreuzer

(accessed 16/11/2018 15:50 AST).

[7] See: Thaler (Wikipedia article).

URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thaler (accessed 16/11/2018 15:56 AST).

[8] See: Portuguese real (Wikipedia article).

URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Portuguese_real (accessed 16/11/2018 15:59

AST).

[9] See: Portuguese dinheiro (Wikipedia

article). URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Portuguese_dinheiro (accessed

16/11/2018 16:20 AST).

[10] See: Mary Ames Mitchell (2015)

Fifteenth Century Portuguese Dinheiro [Money], Crossing the Ocean Sea.

URL: http://www.crossingtheoceansea.com/OceanSeaPages/OS-46-Dinheiro.html

(accessed 16/11/2018).

[11] See: Blair Sullivan, Geoffrey Symcox

(2005) Christopher Columbus and the Enterprise of the Indies: A Brief

History with Documents (Boston, Mass. : Bedford/ St Martin's), p. 45.

[12] See: Ducat (Wikipedia article).

URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ducat (accessed 16/11/2018 16:33 AST).

[13] See: NJ Bridgewater (2017) Gold:

10 Ways to Make Money Using Gold (Abergavenny: Jaha Publishing), pp. 15 –

17.

[14] NJ Bridgewater (2017) Gold: 10

Ways to Make Money Using Gold, pp. 15 – 16.

[15] Image source: Five Guinea coin,

James II, Great Britain, 1688. Public domain. URL: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/d/d9/5_Guineas%2C_James_II%2C_Great_Britain%2C_1688_-_Bode-Museum_-_DSC02761.JPG

(accessed 22/11/2018).

[16] See: British Empire (Wikipedia article).

URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/British_Empire (accessed 19/11/2018 16:48

AST).

[17] See: Federal Reserve Act (Wikipedia

article). URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Federal_Reserve_Act (accessed

19/11/2018 17:02 AST).

[18] See: Mike Maloney (2015) Guide to

Investing in Gold & Silver: Protect Your Financial Future (Scottsdale,

Arizona: RDA Press LLC), p. 217. Download the free PDF from: https://goldsilver.com/promo/freebook/

(accessed 25/11/2018).

[19] See: Investopedia (2018) What causes

inflation, and does anyone gain from it? Investopedia, LLC, updated

January 22, 2018 1:05 PM EST. URL: https://www.investopedia.com/ask/answers/111314/what-causes-inflation-and-does-anyone-gain-it.asp

(accessed 19/11/2018).

[20] See: History of paper (Wikipedia article).

URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_paper (accessed 19/11/2018 12:02

PM AST).

[21] See: History of paper (Wikipedia article).

[22] See: Banknote (Wikipedia article).

[23] See: Bank (Wikipedia article).

URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bank (accessed 19/11/2018 12:10 PM AST).

[24] See: Banknote (Wikipedia article).

[25] See: Banknote (Wikipedia article).

[26] See: Banknote (Wikipedia article).

[27] See: Banknote (Wikipedia article).

[28] Image source: Promissory note, 1774

(MS 376/3). Public domain. URL:

https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/manuscriptsandspecialcollections/images-multimedia/researchguidance/accounting/promissory-07-4285m.jpg

(accessed 22/11/2018).

[29] Nicholas Barbon, Discourse On

Trade, 1690. p.37.

[30] See: Nicholas Barbon (Wikipedia article).

URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nicholas_Barbon (accessed 19/11/2018 13:49

AST).

[31] See: Edwin Cannan (1922) Wealth:

A Brief Explanation of the Causes of Economic Wealth (London: P.S. King and

Son, 1922). URL: https://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/2063 (accessed 19/11/2018

13:49 AST).

[32] See: Joy Blenman (2016) Adam Smith

and "The Wealth Of Nations". Investopedia, September 7, 2016

4:53 PM EDT. URL:

https://www.investopedia.com/updates/adam-smith-wealth-of-nations/ (accessed

19/11/2018).

[33] See: Blenman (2016).

[34] See: Blenman (2016).

[35] See: Jacob H. Hollander (1911) The

Development of the Theory of Money from Adam Smith to David Ricardo, The

Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 25, No. 3 (May, 1911), pp. 429-470 (42

pages). URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1883613 (accessed 19/11/2018).

[36] David Ricardo (1810) The High

Price of Bullion: A Proof of the Depreciation of Bank Notes (London: John

Murray), p. 44. URL: https://archive.org/details/highpriceofbulli10rica/page/n5

(accessed 21/11/2018).

[37] See: Banknote (Wikipedia article).

[38] See: Banknote (Wikipedia article).

[39] See: Dirham (Wikipedia article).

URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dirham (accessed 19/11/2018 14:40 AST).

[40] See: Stefan Heidemann (2011) The

early Islamic Empire and its religion on coin imagery. In Albrecht Fuess,

Jan-Peter Hartung (editors) (2011) Court Cultures in the Muslim World:

Seventh to nineteenth centuries (London; New York: Routledge). URL:

https://www.aai.uni-hamburg.de/voror/personen/heidemann/medien/2011-heidemann-courtcultures2011-representation.pdf

(accessed 19/11/2018), p. 47.

[41] See: Gold dinar (Wikipedia article).

URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gold_dinar (accessed 19/11/2018 14:43 AST).

[42] See: Pound (mass) (Wikipedia article).

URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pound_(mass) (accessed 19/11/2018 14:46

AST).

[43] See: Chris Parker (2016) A short

history of the British pound, World Economic Forum, 27 Jun 2016. URL:

https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/06/a-short-history-of-the-british-pound/

(accessed 19/11/2018).

[44] See: Pound sterling (Wikipedia

article). URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pound_sterling (accessed

19/11/2016 14:57 AST).

[45] See: Central bank (Wikipedia

article). URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Central_bank (accessed 20/11/2018

06:59 AST).

[46] See: Early American Currency (Wikipedia

article). URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Early_American_currency (accessed

20/11/2018 07:03 AST).

[47] See: Early American Currency (Wikipedia

article).

[48] See: Early American Currency (Wikipedia

article).

[49] Image source: Continental One Third

Dollar Note (obverse). Public domain. URL:

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/ff/Continental_Currency_One-Third-Dollar_17-Feb-76_obv.jpg

(accessed 22/11/2018).

[50] See: Early American Currency (Wikipedia

article).

[51] See: Jay Zawatsky (2012) The

Collapse of the Fiat System, The National Interest, March 15, 2012. URL:

https://nationalinterest.org/commentary/the-collapse-the-fiat-system-6639

(accessed 21/11/2018); Julia Limitone (2017) Bitcoin is more powerful than

physical money: Overstock CEO, Fox Business, published November 20,

2017. URL:

https://www.foxbusiness.com/features/bitcoin-is-more-powerful-than-physical-money-overstock-ceo

(accessed 21/11/2018); John Morley (1872), In The Quarterly Review, Vol.

135, July & October, 1873 (London: John Murray), p. 336. See also: Tyler

Durden (2018) Fiat Currency Always Ends In Collapse, ZeroHedge, Mon,

06/18/2018 – 20:55. URL: https://www.zerohedge.com/news/2018-06-18/fiat-currency-always-ends-collapse

(accessed 21/11/2018).

[52] See: U.S. Constitution,

Article I, Section VIII. URL: https://www.usconstitution.net/xconst_A1Sec8.html

(accessed 20/11/2018).

[53] See: U.S. Constitution,

Article I, Section X. URL: https://www.usconstitution.net/xconst_A1Sec10.html

(accessed 20/11/2018).

[54] See: First Bank of the United States

(Wikipedia article). URL:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/First_Bank_of_the_United_States (accessed

20/11/2018 07:26 AST).

[55] See: Second Bank of the United States

(Wikipedia article). URL:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Second_Bank_of_the_United_States (accessed

20/11/2018 07:27 AST).

[56] See: National Bank Act (Wikipedia

article). URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/National_Bank_Act (accessed

20/11/2018 07:32 AST).

[57] See: Confederate States dollar (Wikipedia

article). URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Confederate_States_dollar

(accessed 20/11/2018 07:34 AST).

[58] See: Coinage Act of 1792 (Wikipedia

article). URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coinage_Act_of_1792 (accessed

20/11/2018 09:44 AST).

[59] Image source: United States gold

dollar. U.S. Mint (coin); Heritage Auctions (image) - Heritage Auctions Lot

6787, 9 January 2015. Public domain. URL: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/b/b6/1849_G%241_Open_Wreath_%28rev%29.jpg

(accessed 22/11/2018).

[60] See: United States dollar (Wikipedia

article). URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_dollar (accessed

20/11/2018 09:49 AST).

[61] See: United States dollar (Wikipedia

article).

[62] See: United States dollar (Wikipedia

article).

[63] See: Bretton Woods system (Wikipedia

article). URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bretton_Woods_system (accessed

20/11/2018 09:58 AST).

[64] See: John Morley (1872), In The

Quarterly Review, Vol. 135, July & October, 1873 (London: John Murray),

p. 336.

[65] See: Charles Kadlec (2011) Nixon's

Colossal Monetary Error: The Verdict 40 Years Later, Forbes, Aug 15,

2011, 10:00am. URL: https://www.forbes.com/sites/charleskadlec/2011/08/15/nixons-colossal-monetary-error-the-verdict-40-years-later/#558a84ff69f7

(accessed 20/11/2018).

[66] See: Kadlec (2011).

[67] See: The Economist (2010) Tricky

Dick and the dollar, The Economist, Mar 25th 2010. URL: https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2010/03/25/tricky-dick-and-the-dollar

(accessed 20/11/2018).

[68] See: Robert Nedelkoff (2011) Forty

Years After The “Nixon Shock”, The Nixon Foundation, August 5, 2011.

URL: https://www.nixonfoundation.org/2011/08/forty-years-after-the-nixon-shock/

(accessed 20/11/2018).

[69] See: Nedelkoff (2011).

[70] See: Michael Bryan (2013) The Great

Inflation, Federal Reserve History, November 22, 2013. URL:

https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/great_inflation (accessed 20/11/2018).

[71] See: H Brothers Inc (2007-2018)

Calculate the value of $1.00 in 1971, DollarTimes, 20/11/2018. URL:

https://www.dollartimes.com/inflation/inflation.php?amount=1&year=1971

(accessed 20/11/2018).

[72] See: Robert Kiyosaki (2005) Why

Savers are Losers, RichDad.com, Monday, October 17, 2005. URL:

http://www.richdad.com/Resources/Articles/why-savers-are-losers.aspx (accessed

21/11/2018).

[73] See: H Brothers Inc (2007-2018).

[74] See: CPI Inflation Calculator (2018)

$1 in 1792 → 2017 | Inflation Calculator.” U.S.

Official Inflation Data, Alioth Finance, 20 Nov. 2018. URL:

https://www.officialdata.org/1792-dollars-in-2017?amount=1 (accessed 20/11/2018).

[75] See: Computer Hope (2018) When was

the first computer invented? Computer Hope, 11/13/2018. URL:

https://www.computerhope.com/issues/ch000984.htm (accessed 21/11/2018).

[76] See: Bank of America Corporation

(2018) Bank of America revolutionizes banking industry, Bank of America

Corporation. URL: https://about.bankofamerica.com/en-us/our-story/bank-of-america-revolutionizes-industry.html#fbid=k9IDxSLJ4_R

(accessed 21/11/2018).

[77] See: Bank of America Corporation

(2018).

[78] Image source: Colossus codebreaking

computer in operation. Public Domain. URL: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/4/4b/Colossus.jpg

(accessed 21/11/2018).

[79] See: Mark Gimein (2016) Why Digital

Money Hasn’t Killed Cash, The New Yorker, April 28, 2016. URL:

https://www.newyorker.com/business/currency/why-digital-money-hasnt-killed-cash

(accessed 21/11/2018).

[80] See: Mark Gimein (2016).

[81] See: Jeff Desjardins (2018) Here's

how much US currency there is in circulation, Business Insider,

19.04.2018, 01:30. URL:

https://www.businessinsider.de/heres-how-much-us-currency-there-is-in-circulation-2018-4?r=US&IR=T

(accessed 21/11/2018).

[82] See: Jeff Desjardins (2018).

[83] See: Ed Grabianowski (2018) How

Currency Works, HowStuffWorks.com. URL:

https://money.howstuffworks.com/currency6.htm (accessed 21/11/2018).

[84] Nicholas Barbon, Discourse On

Trade, 1690. p.37. URL: https://archive.org/details/nicholasbarbonon00barb

(accessed 21/10/2018).

[85] See: Andrew Boyd (2018) Who invented

credit cards, Credit Card Compare, July 4, 2018. URL:

https://www.creditcardcompare.com.au/blog/who-invented-credit-cards/ (accessed

21/11/2018).

[86] See: Andrew Boyd (2018).

[87] Image source: Visa, MasterCard,

American Express (CC BY-SA 4.0), uploaded by MB-one (own work). URL: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/c/cc/Credit_card_logos_%282015-12-1816-27-350044%29.jpg

(accessed 22/11/2018). For more information on the license, see:

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/ (accessed 22/11/2018).

.jpg)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment